‘Tis the season for friends and families to come together and share the spirit of goodwill, considering the present, the future and the past. Perhaps channelling A Christmas Carol (the Muppets version of which, incidentally, sets the gold standard); a heart-warming tale set in old London town, where a miserly, hated old man learned the error of his ways and redeemed himself by bringing people together to celebrate life together.

It could be argued that buses bring people together, and that tenuous link is enough to justify me in featuring this 1978 MCW Metrobus today — it is, after all, a very festive colour and did serve in London. Welcome to the Christmas Carchive.

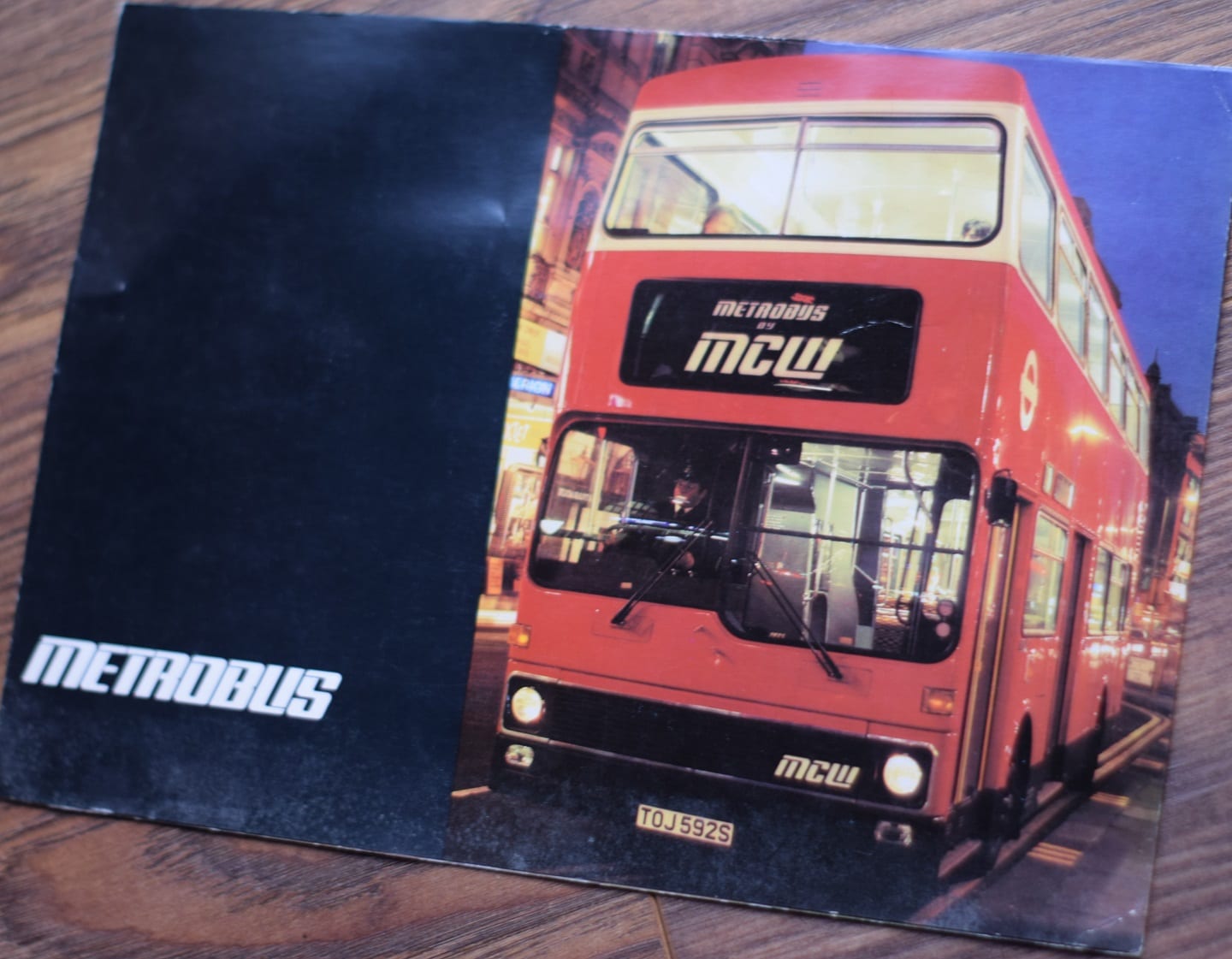

Click the pics to make the buses bigger

“All buses are built to carry passengers. In this sense they are equal — with Metrobus the similarity ends there. Metrobus is different not for its own sake, but because its designers wanted to be certain that it will do its job efficiently, with class and in a style that will create new standards for the future of road passenger transport.”

A bold claim indeed, and one that was particularly brave for MCW (Metro-Cammell Weyman) to make in the wake of its previous bus for London, the Daimler DMS. These were based on Daimler Fleetline chassis, with bodywork produced jointly by MCW and Park Lane, and were plagued by teething troubles that saw much of the London Transport fleet withdrawn somewhat early. The Metrobus was its effective replacement, and this time MCW was going it alone.

MCW was always an ambitious company and has some fantastic vehicles on its CV, including certain London tube trains that were built in ’73 and are still in constant service today. The Metrobus wasn’t the first integral (all-in-one) double-decker bus the firm had offered, either, but the earlier Scania-engineered MCW Metropolitan wasn’t exactly a raging success. The Metrobus, though, used tried and tested components, including a Gardner diesel engine that was widely used in thousands of other private and publicly-run buses and trucks all over the country.

And jolly successful it was, too.

“The MCW asymmetrical windscreen layout combined with a relatively high driving position guarantees the driver a commanding view of the road and constant supervision of boarding and alighting passengers.”

The MCW Metrobus’ chief rival was the Leyland Titan. Rather messily, the old Daimler DMS had used a British Leyland (Daimler division) chassis and MCW / Park Lane bodywork, and so BL intended the Titan to demonstrate just how good a job it could do of a London bus when left to its own devices. As a result, the Titan was very heavily tailored to a London specification, which led to its rejection to many other national fleets.

By being rather less radical, the MCW Metrobus had a bit of an advantage, and when Leyland Titan production began to falter, it usurped the BL product and ended up taking the majority of London Bus sales in the end. In the early 80s, an updated and simplified Mk2 model arrived, spelling the end of the asymmetrical windscreen, but improving reliability and reducing costs.

“An 11-metre (36′ 0″) double deck version with a wheelbase of 6.42 metres (21′ 2″) is also available with uprated axles and suspension. This version, which is suited to certain territories, can also be supplied in one or two-door form, again with either left or right hand drive”.

40 of the latter went to China and were used on ‘luxury’ service, which is something that anybody who has ever travelled by Metrobus might find difficult to believe. That said, much of my MCW experience was on the West Midlands Travel buses of Coventry, and many of that city’s roads felt like they had been recently ploughed.

Later, a third axle no doubt contributed towards comfort, and a 12-metre Super-Metrobus prototype led towards an 11-metre ten-wheeler that would become popular in the Hong Kong area. After withdrawal, many ended up having a quick roof chop for sightseeing duties in Australia where the Super-Metrobus’ long top deck was a boon. A handful ended up back in the UK where they came in handy for high-capacity school bus service.

Metro-Cammel Weymann sadly fell apart at the end of the 1980s, when its parent company decided to sell off various divisions. The Metrobus operation ended up in the hands of Optare, a Yorkshire-based coach builder which is now, most ironically, 75% owned by Ashok Leyland — the Indian offshoot of British Leyland. Everything seems to be connected somehow in bus circles.

And as for this brochure, well, it feels like an actual historical artefact. This brochure was used to market and publicise a thing that would become a very common sight on London’s roads — never as iconic as the AEC Routemaster, but no less important to the city’s residents.

(All images are of original publicity material, photographed by me. It’s very doubtful whether the copyright actually belongs to anybody any more. Perhaps I’ll claim it for myself. Merry Christmas)

Leave a Reply